Reproducible analysis: environment

Debug your app, not your environment.

Docker’s slogan is a good one. It’s a pity when you can’t focus on the work at hand because of environment issues. You end up trying to fix both your code and the environment at the same which frankly is just a world of pain. Docker helps with creating a reproducible environment so you can count on the environment being always in the state you want.

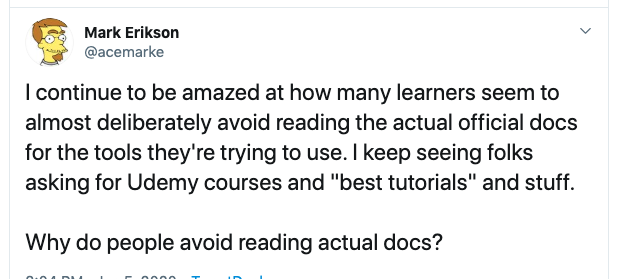

Small remark, the official Docker documentation is really good, you don’t really need a lot of extra info. However, this simple example really helper me on my way.

Dockerfile

The Dockerfile is actually the only file you need to run anything in Docker. From the official documentation:

Docker builds images automatically by reading the instructions from a Dockerfile – a text file that contains all commands, in order, needed to build a given image.

So a Dockerfile is like a recipe instructing Docker how to build your image. An image is a template of what your environment will look like. Don’t confuse images with containers. Containers are instances of images. You can have many containers based on a single image.

A Dockerfile must begin with a

FROMinstruction. The FROM instruction specifies the Parent Image from which you are building.

You rarely start from scratch because most of the times you’re only interested in keeping constant some aspects of your environment. However, uff you really really want to start from the ground up you still can by putting FROM scratch at the top of your Dockerfile. Docker Hub is the default images source for FROM. In the beginning it was not clear for me where FROM got its base images from but I found the FROM section in the Dockerfile reference surprisingly paltry.

The image I based myself on is the one by rocker. All rocker images are hosted on dockerhub. There are basically 2 types of Docker images provided by rocker:

- unversioned

- versioned

Unversioned means the latest R version is used. To keep it as reproducible as possible I’d like to use the exact R version as used locally for this series. You can easily find your R version on the command line:

R --version | grep "R version"

I am running R version 3.6.1 locally (nicknamed “Action of the Toes”, apparently a reference to this). To be sure I’m using the Docker image and not the local version of R I install the Docker image with version 3.6.2. This is the latest version available and was released end of 2019. There are different flavors available within each R version including a version with tidyverse and devtools which is exactly what I needed. tidyverse and devtools together cover a large part of the packages used in the reproseries analysis.

It’s important to note additional packages can only be installed with the R install.packages function and not apt, the Debian packaging tool. R is installed separately from the R version already bundled with Debian so if you would use apt you risk ending up with 2 different versions of R.

Long story short, we can add the following at the top of our Dockerfile:

FROM rocker/tidyverse:3.6.2

docker build

We can already try our image out, even though at the moment it’s just a copy of the rocker image. Running docker build -t repro . shows the rocker image is fetched correctly. The build command only takes 1 mandatory argument which is the PATH for the build context. The . defines where the build context can be found. We pass a name for the image as well (using -t), if not you always have to refer to the image id (which is hard to remember).

If you want to make sure the image has been created correctly afterwards you can run:

docker images | grep repro

The build process could be sped up a bit by using a .dockerignore file. If you build the Dockerfile without using the .dockerignore file the first line displayed is:

Sending build context to Docker daemon 256.3MB

This means about 250MB is transferred. Some files transferred are not used. I didn’t spend extra time on optimization so I just kept the .dockerignore file empty.

Installing additional packages

Now we have an image with R and the tidyverse packages installed. However, in our analysis we did more. We used other R packages as well as you can see in the R package description. We also created scripts to run our analysis for the orchestration post in this series. Let’s try to run a script which uses a package we haven’t installed yet (timetk for example) and see what error it gives.

We first have to install our own package reproseries. This can be done in 2 separate ways:

- by copying a tarball

- by using

devtools::install

The devtools way is by far the easiest.

tarball

Create a tarball of the package by running R CMD build reproseries. Note you have to run this command from the directory that contains reproseries (so a level up the root directoy).

devtools::install

First we copy our local reproseries repository to the Docker image by adding this to the Dockerfile:

COPY . /reproseries

Next the following line can be added to the Dockerfile:

RUN R -e "devtools::install('reproseries')"

This way devtools takes care of the installation. The -e option just tells R to execute the expression within quotes as if a R environment would be open.

It’s important to pay attention to the difference between RUN and CMD. RUN runs only once while building the image, CMD runs each time you run a container.

Run analysis

For running the analysis I could have leveraged the work done in the orchestration post. Orchestration means airflow which also means Python. Setting up the Python environment turned out to be slightly more involved than planned. It’s worth a post on its own. As a workaround I created a file analysis.sh which mirrors what the temperatures.py DAG did. First it tidies and transforms the data and based on the transformed data the visualization and modelling part is ran.

Getting the results back locally

Now everything is ready to run the analysis:

- R is installed

- our repository has been copied to the Docker image

- additional packages needed have been installed

- the analysis script has been added as the default run command

If we run the container now, the analysis runs just fine. Which is great but where are the results? They’re still in the container but not on your local machine. To get the Docker container to share its data with your local machine, you can create a volume when running the container.

Push container to Docker Hub

As the cherry on the cake, I want everything to be able to reproduce my analysis as easily as possible. That’s why the image is available in the reproseries repository on Docker Hub.

Pushing an image to Docker is easy:

- login to Docker Hub

- tag the image

- push it to Docker Hub

To test the image out for yourself:

docker run -e PASSWORD="" -v LOCAL_DATA_FOLDER:/data isaacverminck/reproseries:repro

Don’t forget to specify a password (you’re prompted to do so) and to specify the folder on your local machine where you’d like the data to be stored.

Summary

Using Docker isn’t as complex as it sounds. You just need to know what a Dockerfile is, what the basic commands are you can use in a Dockerfile and the difference between an image and a container.

As usual the code can be found in the reproseries repository on GitHub.